Theatre of Violence: What Vijay Tendulkar Would Have Written Today

This story first appeared in The Quint

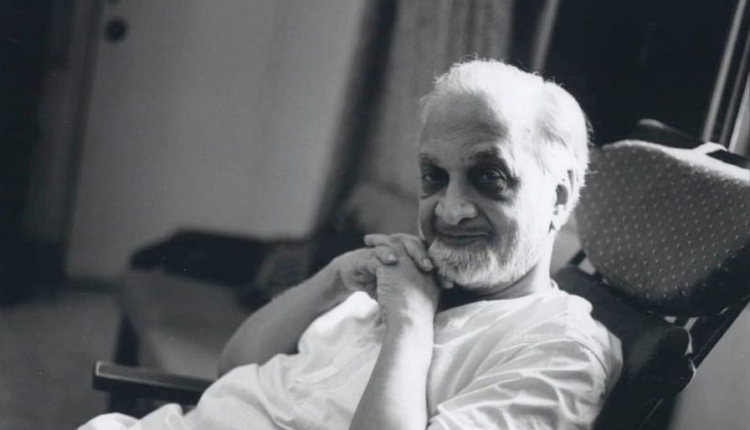

Nishtha Gautam, journalist and SAWM member writes about how in today’s time the exceptional play-write Vijay Tendulkar would have written. He who always defied propaganda and never sacrificed his empirical understanding of the society before any agenda. An interesting read indeed.

A wily ruler, a corrupt and cruel policeman, an innocent girl at the receiving end of a powerful man’s lust, and some enraged Brahmins. The onstage and offstage lives of Vijay Tendulkar’s Ghashiram Kotwal could very well have been pieced together from the mosaic tiles of contemporary events. The everyday violence on the streets owing to the recent anti-CAA protests could have given Tendulkar, the Antonin Artaud of Indian theatre scene in the 1970s, his characters one too many.

Like Artaud, Tendulkar philosophised about and depicted violence and cruelty through his plays. Talking about Artaud’s craft, philosopher Jacques Derrida had noted that he was an embodiment of both aggression and reparation. The same could be said about Tendulkar who laid bare the ugliness of human behaviour minus the moralising.

Equal Opportunity Offender

No wonder, then, that his plays engendered controversy and even violence. What sets Tendulkar apart from many of his contemporaries and successors is the fact that he was routinely attacked by people on both the ends of the spectrum. While a bunch of Brahmins, upset at his depiction of Nana Phadnavis in Ghashiram Kotwal beat him up inside the Express Group office, a dalit man once threw his chappal at him for portraying dalits unflatteringly.

Interestingly, the very references to Peshwa rulers’ debauchery that inspired the ire of Pune Brahmins were also made by none less than Lokmanya Tilak in his assessment of the late Peshwa rule in Maharashtra. Historical facts never deterred the raging Brahmins who saw the play as maligning their community.

The question of women’s honour became a battlefield and women themselves chose sides.

The play outraged the sensibilities of different groups for different reasons. The Leftists saw it as espousing the capitalist idea of exploitation of sex. The middle classes were outraged at the alleged irreverence towards the institution of marriage. Champa’s characterisation angered the backward castes, while the protagonist Sakharam, a brahmin, did not impress the brahmin community.

Tendulkar’s Experiments With Violence

Tendulkar saw violence as a primordial presence in the human society. His theatre was not to shock or awe but to represent men and women with all their foibles that were conventionally hidden behind an acceptable facade. There is a great deal of honesty about his intent.

For Tendulkar the process of writing was as integral to his lifestyle as other life processes. “I wrote like a man seized by a fever, whose head was full of the hallucinatory clamor of many stories. I kept myself alive, and kept writing. There were no boundaries left to separate writing from living. Like breathing, seeing, and speaking, writing had become a law of the body,” he once said.

Violence, whether domestic, sexual or societal, provided him with a clean canvas which he painted with myriad hues of emotions or peculiar mannerisms of characters. Tendulkar’s eye for quirks beneath normalcy was his biggest strength. About his almost clinical observation and enviable ability to recall, he once stated, “I do not have to exert myself to do it, it happens automatically. Everything gets recorded and stored in the computer of the brain. I do not have to call for it as I write. It comes by itself.”

Rejection of ‘Agenda’

What his acute observation skills ended up teaching him was rather significant: his passionate rejection of tribalism or collaborationism of any kind when it came to his writing. His commitment to a just society never blurred his vision towards the fallibility of causes and those who espouse them.

Tendulkar said at a Sahitya Akademi event in 1989, “My own feel of life has taught me that life is pretty rough and complex – at times too complex to be generalised and understood. I have developed a bias against all generalisations.” No wonder, then, that his dalit characters are not merely meek and pitiable victims of structural violence. They can also be the perpetrator of violence and display abhorrent traits.

In the same Sahitya Akademi speech he admitted to being written off as a writer of the Left by his contemporary Leftists. He was often accused of being too pessimistic and cold while depicting the power relations between the exploited and the exploiter. He did not care for how his characters would be perceived by the general public.

“As a writer I feel fascinated by the violent exploited- exploiter relationship and obsessively delve deep into it instead of taking a position against it. That takes me to a point where I feel that this relationship is eternal, a fact of life however cruel, and will never end,” he said.

His view of the society was part Hobbesian and part Van Gogh-esque: violence is omnipresent but each one of us is violent in a unique way. Perhaps, writing today, he would have given us a non-binary anatomy of street violence perpetrated by both the State and the protestors. Had he written about the anti-CAA protests across the country, his stories would not have lionised either the protestors or the persecutors. In Tendulkar’s literary universe, there are no heroic heroes, only fallible men and women. Few liked it then, fewer would favour it today.

Unfortunately, today he would not have found any takers in either Jamia Millia Islamia or in the hallowed portals of policy making.