In Tamil Nadu, A 400-Year-Old Tradition Of Shadow Puppetry Struggles To Survive

For many in the neighbourhood, it was an experience worth cherishing. A local woman had come after sending her kids to their tuition classes. “I was just curious,” she said matter-of-factly. There was another one, begging her seven-year-old son, who was complaining of leg pain, to stay back a little longer. “It is not always that we get to see such performances,” she told him. Some had sauntered in, drawn by the different kind of sounds from the stage.

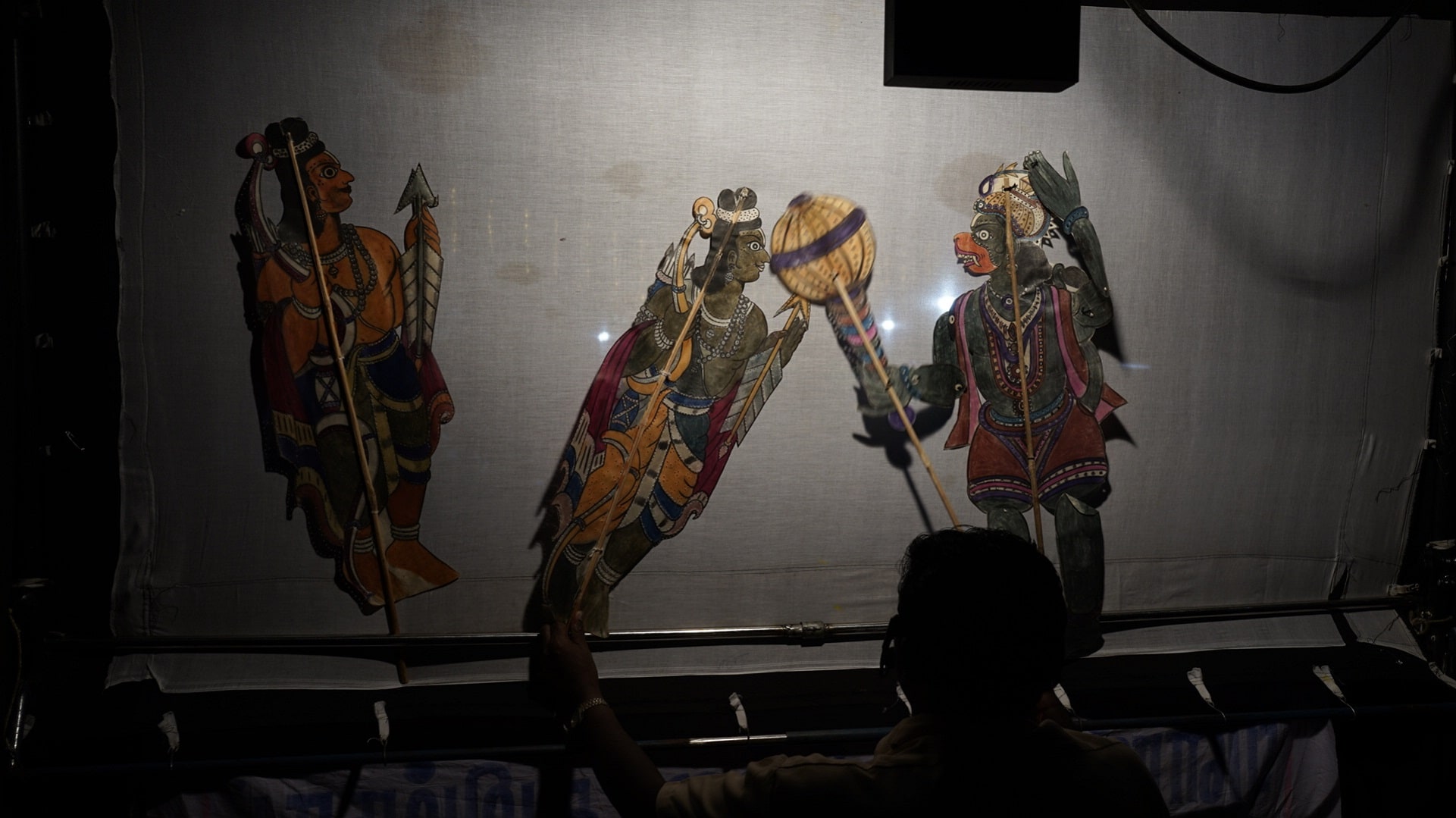

What really stood out among the medley of performances was Thol Pavai Koothu (shadow puppetry) by Kalavalarmani B Muthuchandran and his troupe from Kanyakumari district. A dying art in Tamil Nadu, Thol Pavai Koothu has very few practitioners — Muthuchandran and his family being foremost among them.

An ancient form of story-telling, Thol Pavai Koothu involves using figures made of goatskin to enact a story. “That is where the name is derived from. In Tamil, thol means skin,” Muthuchandran says.

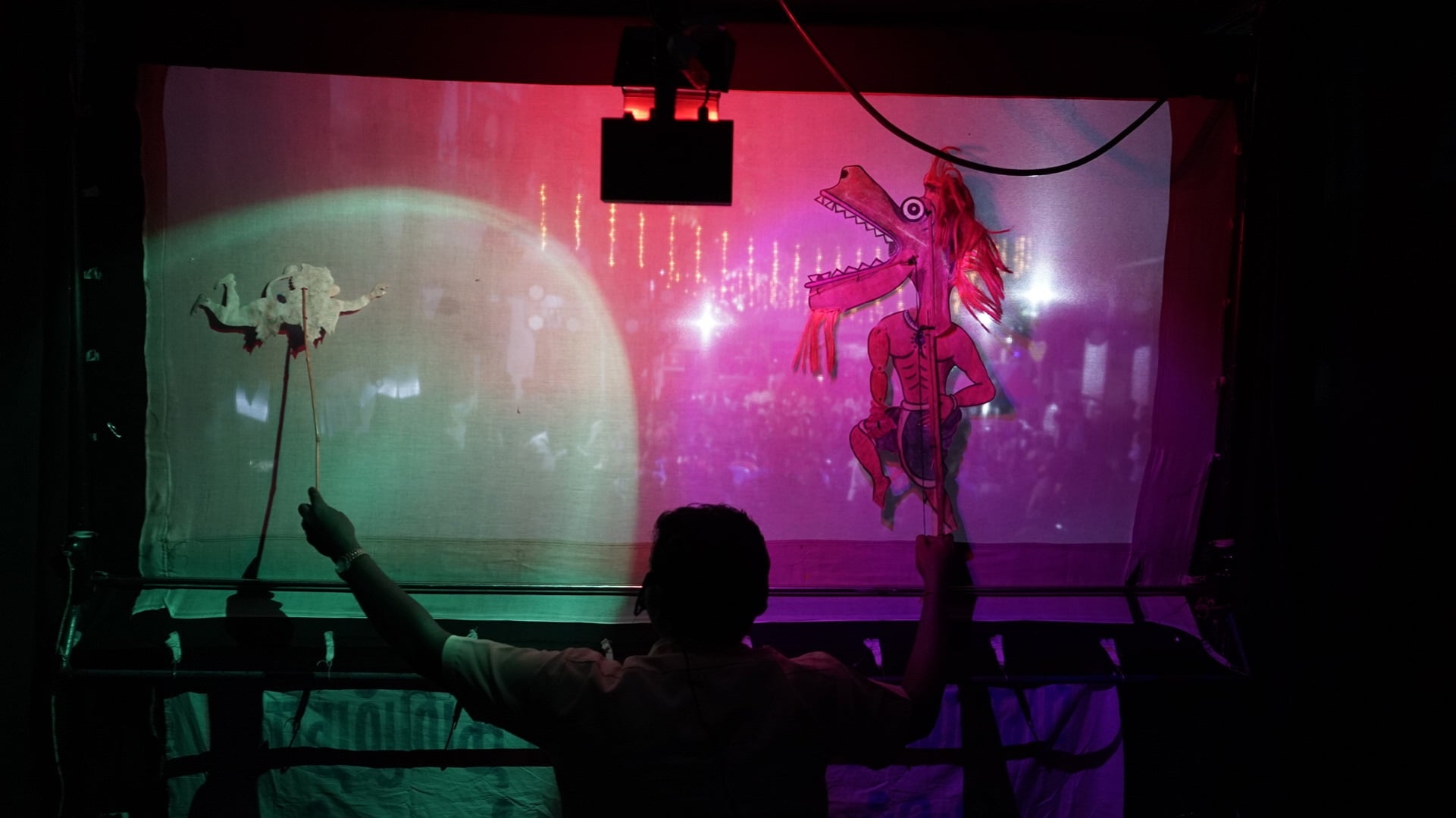

His one-hour performance had a wide-ranging arch — from a variety of scenes from the Ramayana, to contemporary issues like the importance of not using plastic. Behind the translucent screen, Muthuchandran deftly used his hands to move the puppets around and bring his various characters to life. His effortlessness in enacting scenes that appear difficult, including the viswaroopam of Hanuman when he meets Sita in Ashokavanam, or later, of a man climbing a palm tree, speaks volumes about his expertise in Thol Pavai Koothu.

“It is not something you learn in school. I have learnt it from my father Balakrishna Rao, I have seen him making the puppets, and giving voices to them. I have learnt it from a distance while accompanying him on his shows, doing music,” he says.

Muthuchandran’s performance was interspersed with a liberal dose of humour, often sending the audience into splits. For many youngsters, it was a first-of-its-kind experience.

“Thol Pavai Koothu is 400-year-old folk art. We have been doing it for over 15 generations. I have been able to trace it up to six generations,” Muthuchandran explains, listing the names of his forefathers. Up until three decades ago, his family had been nomadic. “I decided to build a house in Kanyakumari and settle down because I want my son to study. It was difficult for us to get an education since we kept moving from one place to another. I did not want my son to meet with the same fate.” Exactly 28 years ago, Muthuchandran decided that his family needed a home they could call their own.

His family’s story dates back to the pre-British era of the Thanjavur Sarabhoji rulers. “We migrated from Maharashtra during their period because the kings were patrons of folk art. But after the British took over, we were left in the lurch and many families like ours had to leave Thanjavur.” The families spread across Tamil Nadu, often travelling from one place to another in search of work.

Muthuchandran’s is among the very few families today to preserve the art of Thol Paavai Koothu. “My ancestors toured throughout Tamil Nadu, camping at a village to do a performance and then moving to another. Today, from Kanyakumari, I travel the length and breadth of Tamil Nadu. But I am afraid I will be the last in my family. My son is pursuing a Bachelor’s degree in History, I’m not certain what he plans to do.”

Tholpavai Koothu is a hugely demanding art. It requires an entire family to be involved, in order to put up a decent performance. “What you see on stage is the final act of a very long process.”

The arduous process begins with procuring goatskin and treating it for days. “We either keep it immersed in water and let it lie around for a couple of days. After this treatment, the goatskin turns dry, into something like paper and we draw and make puppets out of it,” Muthuchandran explains. The process typically takes about a week. While it is easy to make puppets for a show like the Ramayana, which Muthuchandran has learnt from his father, he employs his creativity to make puppets for contemporary subjects. Muthuchandran can also speak in 28 to 31 different voices to suit each character on stage.

“It is not always easy to establish the difference between one character and another through voice. But typically, only one person will be behind the screen doing it. I always handle all the male voices needed for the show. My family members help in coordinating the music and other elements.”

Muthuchandran believes the contemporariness he has managed to inculcate in his art has helped it survive.

“There were times when my ancestors would do performances revolving around the Ramayana that would last for three hours or more. Today, it is not possible. People are neither interested in the Ramayana, nor in having such long performances.”

He draws from the stories he hears told by people he meets on his travels. “I go to villages where I see a family finding it tough because the head of the family is an alcoholic. I speak to people and find out why plastic is harmful. My parents are my first gurus, but I have also been fortunate enough to be guided by AK Perumal, a scholar in folk arts. He has often helped me incorporate contemporary subjects into my performances, giving me material and ideas.”

But the contemporariness notwithstanding, Thol Pavai Koothu has its own set of challenges as a full-time occupation. “We hardly get four to five chances to perform each month. This is not enough to sustain a family as big as ours,” Muthuchandran says. The fear of family tradition being abandoned after him is palpable in his voice. “I can understand if my son does not want to pursue this art,” he says, even as a young girl walks up to him, to thank him for the performance. “I have never seen something like this,” she tells him. “But this is why I want him to pursue it, at least part-time,” says Muthuchandran.

All photographs taken by G Rajaram