Backstory: Women’s Day Thoughts: Lives on the Edge of Blank White Space

The most important image of women in the media was their “non-image”: Margaret Gallagher’s succinct formulation dating back to 1981 inspired some of us in journalism to look a little closer at what was then termed as “women’s representation in the media”. The obverse side of that non-representation, we discovered soon enough, was the deliberately constructed “on-image”. An image, always on, that conformed to market requirements, patriarchal assumptions, or both. As the song went, being so much older then, we thought we were wise enough to correct such representations by systematically critiquing them. That was how the Women and Media Committee of the Bombay Union of Journalists actually sent a team comprising Meena Menon, Geeta Seshu and Sujata Anandan to Deorala, Rajasthan in 1987, because we were so dismayed by the reportage on the sati incident. Meanwhile, three of us — Padma Prakash, Teesta Setalvad and myself — pored over stacks of newspapers and magazines for days to “review press coverage” on the Roop Kanwar burning. Our “findings” were published in a small pamphlet and gave us a triumphant sense of having countered the media-fueled avalanche that glorified the tragic event.

How audacious, we were, how delusional. Over the next few years the media had emerged as the prime site for the consolidation of both markets and religio-nationalism in the country, with gender playing a pivotally symbolic role. Interesting, therefore, to read Professor Maitrayee Chaudhuri observe in a interview given to The Wire that the “hypervisibility” of women in the media today does not “necessarily add up to a greater gender-just society” (‘Interview: ‘We Have Shifted From an Era of Invisibility of Women to Hypervisibility in Media’, March 1).

What we do have is a flourishing of third generation feminism in the online space by young women journalists who intuitively understand the importance of the stuff that does not figure in mainstream media. ‘Feminism in India’, self-defines itself as “an intersectional feminist platform that amplifies voices of women & the marginalised using art, media, culture, tech & community”, while another, ‘Ladies Finger’, sees itself as “delivering fresh and witty perspectives on politics, culture, health, sex, work and everything in between…” We can only hope that such attempts at defying the mighty mainstream may just be harbingers of more gender equal, less power-driven, media content. After all, to borrow from Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale, “We were the people who were not in the papers. We lived in the blank white spaces at the edges of print. It gave us more freedom. We lived in the gaps between the stories.”

And the gaps within stories, is also important, one could add. It is often only when those who live in the gaps within the story come into view, that the story itself acquires life. Recently we have had a spate of news reports about UP chief minister Adityanath’s police which, having borrowed a bloody page from the Mumbai Police’s killer squad of the 1990s, are now busy eliminating people in cold blood in the name of fighting crime. Most of these news reports come with a patina of approval over how the chief minister is being tough on local mafias, each one of them read as if it was a drafted in a police chowki. They make you wonder whether the reporters behind them had even a nodding acquaintance with the Constitution.

Do they realise that such “officially authorized” blood-letting is a complete violation of a civilised criminal justice system? It is against such an apology for news stories that The Wire feature on encounter killings in Shamli district must be read (‘A Chronicle of the Crime Fiction That is Adityanath’s Encounter Raj’, February 24). It is not just the aggregation of 14 cases of encounter murders in the district of Shamli and a careful documentaton of the chilling, cookie-cutter pattern that marks the killings, that is valuable. Its strength comes from the women who live in the gaps of this story — wives and mothers of the dead men, rife with grief, anger and helplessness. If there is one story that should remove the celebratory smirk on the face of the state’s chief minister that currently adorns a UP government poster showcasing his “1038 encounters”, it is this one. Such a story also testifies to the twinning between gender representation in the media as professionals and gender representation in media content. Being a woman journalist allowed the reporter in this case to go beyond the front door and enter the rooms where women sit on charpoys and weep.

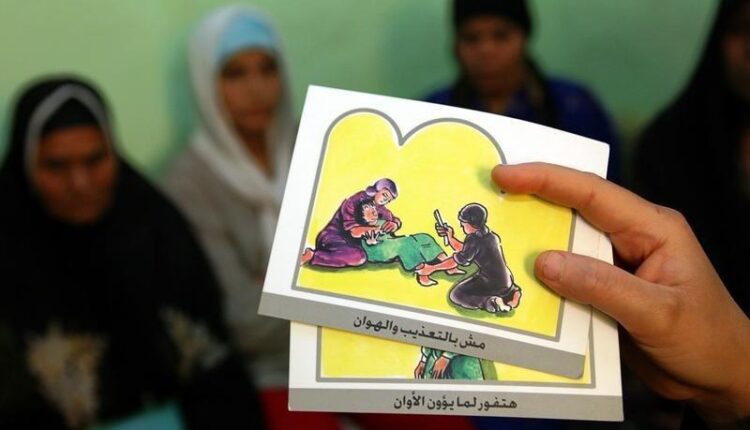

Ditto for stories on female genital mutilation (FMG) which, we had always maintained, took place in Egypt or Sudan. It was over the last year or so that, thanks to the hard work of some women within the community, that we now know that FMG is not alien to India. These activists have subsequently set up the ‘Speak Out on FGM’ collective (‘Voices of Resistance Against Female Genital Mutilation in India Grow Louder’, December 24, 2017). The collection of data through a year- long study now reveals a far larger presence of FMG in the country than previously thought (‘With Data, an Attempt to Lift the Veil of Secrecy Around Female Genital Mutilation’, February 7).

It is not just the Suleimani and Alvi Bohras that practice FMG, but Dawoodis and some sub-sects in Kerala. What is shocking is that the Narendra Modi government has denied the existence of the practice in India. Why? Surely the Union Women and Child Development Ministry should respond to an inquiry report that had in-depth interviews conducted with 94 people from the community? Could it be a “vote bank” issue here? After all, the Bohras have on occasion been used to buttress Modi’s secular credentials, some even being flown to locations such as Madison Square to hear first-hand the prime minister’s many orations on foreign soil.

Therefore when BJP’s women ministers carpet bomb the media with their long pieces on this government’s women-centric development or the prime minister tweets that women “continue to inspire generations”, what really does all this mean? When 8-year-old from the Bakarwal community in Jammu is found raped and murdered, allegedly by a local police officer, and local BJP cadres come out on the streets waving tricolours protesting the arrest of a “nationalist”, we need to unpack this communally spawned outrage. When the Goa chief minister says women drinking beer is disturbing him (‘Goa’s Biggest Problem Really That Women Drink Beer?’, February 11), we need to ask him why he doesn’t demonstrate the same concern about the drug mafia destroying lives in his state. When three-year-old girls are exposed to toxic words directed at the Muslim community (‘Our Three-year-Old Daughter Should Know What it Means to be Hindu, Right From her Childhood’, February 7), we need to interrogate where this Hindutva model of “women’s empowerment” is taking us.

What can be stated with certainty is that it is not from such a space that “bad girls” who challenge the system emerge (‘Forget the Binary of ‘Good Girl’ or ‘Bad Girl’, the New Women Against Sexual Violence Are Here’, March 3). Or if they do, it would need the persistence of those admirable young women of a Haryana university (‘How Girls in Rohtak’s Maharshi Dayanand University Rose Against Curfew Timings, and Won’, February 28) who defied the attempts of university authorities to keep them like caged birds in hostel rooms until they are ready to be delivered to their prospective husbands with due ceremony. The irony of their situation was highlighted by one student who pointed out that while their teachers always taunt them for talking to boys, sexual harassment on the campus continues unchecked and does not seem to bother anyone.

Emerging from these pressure cookers of patriarchal control that our universities and their hostels are proving to be in order to achieve a self-affirming existence is an obstacle race, as top-notch energy physicist Dr Swapna Mahapatra (‘A High Energy Physicist in Odisha Probes Into the Interrelated Universe’, March 7) well knows. She herself chose not to have children in order to keep up with her scholarship and expresses surprise as to why those in the emerging generation don’t seem to make such choices.

In her brilliant 1929 book, A Room of One’s Own, Virginia Woolf imagines what would have happened ‘If Shakespeare Had a Sister’, and goes on to say that “it would have been impossible, completely and entirely, for any woman to have written the plays of Shakespeare in the age of Shakespeare.” It seems similar for women in science in our day, because apart from leaving the stereotypes of patriarchal domesticity behind, they would also have to negotiate the huge negative stereotype that professor and supervisors as well as peers harbour: female students just don’t make the cut.

Journalism that makes visible the lives, work, and achievements of India’s women scientists deserves a special place in our mundane, black-and-white world of current affairs.

What makes a thinking journalist? Neelabh Mishra may have passed on, but his life and work provide an interesting template that privileges calm contemplation in the midst of the dizzying carousel of news creation. The piece, ‘Neelabh Mishra: A Discerning, Calm Voice Falls Silent in an Age of Simplistic Views and Noise’ (February 28) noted that history which makes one conscious of the continuity of time is the natural foil for journalism with its direct connect to the present. In a media world where self-projection is the norm, the capacity to voluntarily step away from the klieg lights and choose a medium and language less bristling with the accoutrements of power, is a valuable example that the late journalist offered those he left behind.