It is Friday afternoon at 6, Zi Wa Ka Road, about a kilometre away from Shwedagon Pagoda, Theravada Buddhism’s stunning showpiece in the middle of Yangon, Myanmar. Men, women and children are streaming in and out through the gate, which is fashioned to look like two minarets, with a grilled arch on top made of cast iron.

On the arch, wrought in iron and painted over with gold colour are the words: “Dargah of Bahadur Shah Zafar — Emperor of India 1837–1857”. At this unassuming address, under the glow of a great golden pagoda, but far away from his beloved Delhi, is where the Mughal empire came to a quiet, unremarkable end with Zafar’s death in exile in Yangon, in 1862.

But more than 150 years after being secretly buried by his British jailors at this place, where he was under house arrest in a small four-roomed accommodation — a contrast to the grandeur of the Red Fort, his previous abode — the dargah is a living monument.

The Friday namaz has just ended in the hall next to the dargah. Three days after Eid, people are still in holiday mode, the atmosphere is festive. A fragrance of roses and perfume fills the air. Families and friends are sitting on the cool floor, handing out food from lunch packets or from the canteen on the premises.

“We come regularly to pray at this dargah,” says Zainab Bibi, who identifies herself as a Burmese Muslim and converses in a mix of halting Hindi and English. “I come every Friday. I take a bus from near my home in Mingalar Tang township (a Yangon suburb). Today, I have come with 12 of my friends. We read the Quran together, and we came for Quran Khatam.” Her friends speak only Burmese. The pensioner, who used to work in a bank before retiring a few years ago, explains that to the local people, Zafar is not so much a king as a “baba”.

“He may have been emperor of Hindustan, but he was greater than that. We call him ‘baba’ because he was so learned, he knew everything. He wrote beautiful poems. There is no other baba in the world like him. Here, when people ask for dua, they are granted their wishes – job ka dua, bimari ka dua, padhai ka dua,” says Zainab Bibi.

Such is the attachment of Myanmar’s people to the dargah that sometime in the last decade, when India contemplated broaching the return of Zafar’s remains to Delhi, the government was told by its diplomats in Yangon to drop it as “there would be riots in Myanmar” if that happened, according to one former official familiar with the matter.

A portrait of Bahadur Shah Zafar and his two sons with a British Officer.

A portrait of Bahadur Shah Zafar and his two sons with a British Officer.

Muslims comprise approximately 2.3 per cent of Myanmar’s 50 million population, excluding the Rohingyas who were not included in the last census. The country’s Muslims are a rich and complex genealogical mix — they have Chinese, Persian and South Asian ancestry. They speak a variety of languages. Tamil Muslims settled in Myanmar during the colonial years, when the British encouraged people from India to immigrate to what was then known as Burma. Rakhine’s Kaman, or Kamein Muslim, who are different from the Rohingya, are recognised as a separate ethnic group in Myanmar’s officially accepted ethnicities.

Outside the Rakhine, where the Rohingya used to number about one million before their exodus to Bangladesh in 2017 — about 7,00,000 Rohingya now live in refugee camps in Cox’s Bazaar — Yangon and Mandalay have the largest Muslim populations in Myanmar. Since 2012, after the first anti-Rohingya violence in Rakhine, communal tensions have surfaced in other parts of the country where the majority Buddhists used to live in integrated communities with Muslims, Hindus and Christians. Myanmar’s tryst with democracy began with a wave of Islamophobia and the unleashing of racial prejudices — some say when the military loosened its grip, it also let loose forces of Buddhist extremism, such as a group called 969, to hobble the civilian democratic leadership. Communal clashes erupted in the footsteps of Ashin Wirathu, who set up the anti-Muslim 969, and is also a leader of the now dismantled Buddhist extremist group Ma Ba Tha (Protection of Race and Religion).

In 2013, some months after violence between Rohingya and Rakhine Buddhists in 2012, Meiktila city, near Mandalay, was the scene of riots, in which over 100 people, mostly Muslims, were killed and thousands had to flee their homes. Five years later, the town is still tense, though well-meaning citizens are involved in conducting inter-faith camps to rebuild the community. Animal sacrifice in the town has been banned. Seven of 14 mosques in Meiktila have been shut down. Muslim residents of the town do not want to be seen talking to outsiders, and say they are being watched all the time, by “authorities” and by “Buddhist hate-mongers”.

Multi-cultural Yangon, where each step feels like a walk through an exhibition of diversity, has also not been immune to communal tensions, though there has been no flare-ups.

Like majoritarian populations elsewhere, Buddhists, who make up 80 per cent of Myanmar’s population, believe that their religion is about to be wiped out. At a meditation centre in a quiet residential area of Yangon, a senior monk says “everyone has a duty to protect their religion from extinction” but attacking people of other religions is not the way to go about it. Asked if it was alright for Buddhists to use violence to protect their religion, the monk gets upset and says his words are being misunderstood and stops the conversation.

The people sitting around at Zafar’s dargah are clearly uncomfortable discussing communal relations in Myanmar. “It’s nothing serious,” says Kader Moiudeen, a cab driver and a car salesman, who has recent roots in Ramanathapuram in Tamil Nadu, changing the subject quickly to how he and his family members would like to make a trip to India some day. “Isn’t this like the Nagoor dargah in Nagapattinam?” one of his uncles asks, thrilled to meet a Tamil-speaker from India. “I really want to visit Tamil Nadu.”

Maulvi Nazir Ahmed, who has officiated at Zafar’s dargah since 1994 — before that he had been the Imam at the Malabari Masjid in Yangon for 10 years from 1984 — eagerly shows visitors around the place, keeping up a running commentary on how the British had hidden Zafar’s real resting place by covering it up with turf.

It was only in the early 20th century, after protests in Yangon, that a stone was set up at a place thought to be “near the site” of Zafar’s grave. Another stone marked his wife Zinat Mahal’s purported grave. For years, that remained the place on the premises where worshippers gathered. The real burial site was discovered in 1991, when a portion of the premise was being dug up for the construction of the prayer hall. It was properly restored after that with financial assistance from India, and lies below the prayer hall.

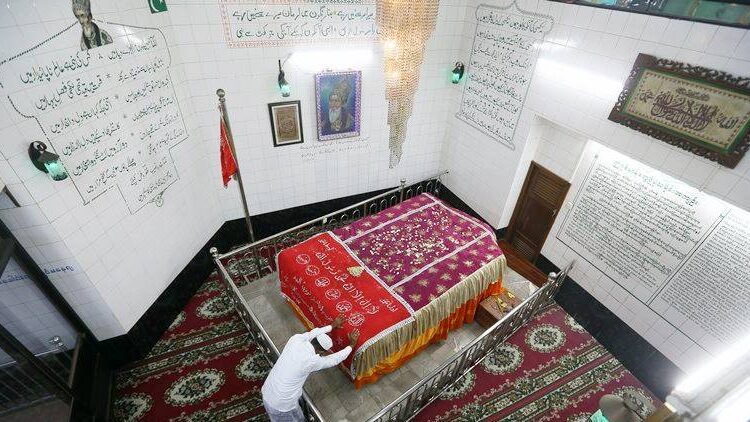

The grave, nine steps down from the prayer hall, is covered by chadars that worshippers bring with them as offering. Rose petals are strewn over the chadars. Worshippers kneel next to it, touch their heads on the stone for a couple of minutes before moving on.

The room where the old graves are is still in use. People sit around the tombs, and pray quietly, their eyes closed in meditation.

On the walls are photographs of Zafar with British officials, of his wife and sons. Below, in a room next to the real grave, are photographs of every Indian and Pakistani leader who have paid a visit to the dargah. Prime Minister Narendra Modivisited the place in 2017. Ahmed goes past each photograph pointing out the VIPs and intoning the names.

According to a former diplomat, the story goes that Pakistan’s former President, General Parvez Musharraf, offered a huge sum of money for the custodians of the dargah to include “and Pakistan” after “Emperor of India” on the gate. But the Indian side prevailed upon the Myanmar government-appointed management not to accept the money.

Zafar’s poetic lament — Kitna hai badnaseeb Zafar dafn ke liye/Do gaz zameen bhi na mili koo-e-yaar mein — about not finding a final resting place in his beloved homeland, is also engraved on the walls of the dargah.

A dozen years ago, when a group of ardent campaigners in India pushed the government to bring Zafar’s remains to Delhi, they believed it would be a befitting way to honour not just him, but also the composite and secular culture of pre-1857 India that his rule epitomised. But, in these troubled times, it seems Myanmar needs Zafar just as much.

source: https://indianexpress.com