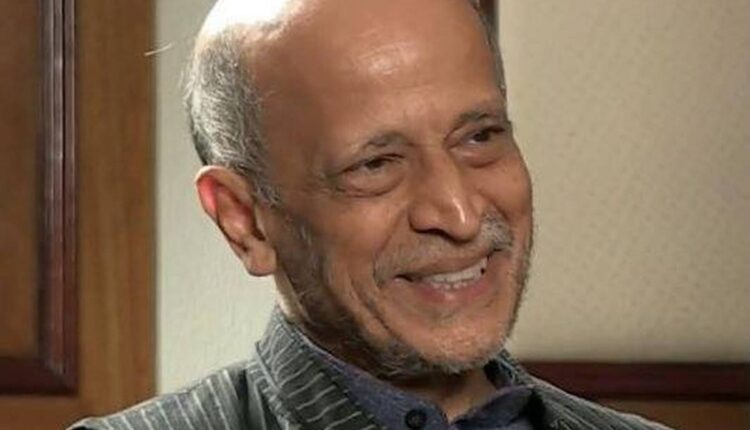

Darryl D’Monte (1944-2018) Perceptive, Compassionate and Always Professional

Old school but open to new ideas, friends, colleagues and acquaintances recall a model journalist

The Talent Spotter

Darryl was a down-to-earth guy, the right person to take over as Resident Editor of The Times of India (still) Bombay in 1988/89. It was a time of high drama courtesy the arrival of Samir Jain who turned the Old Lady of Bori Bunder on her head, Victorian petticoats and all. If that’s an image not meant for the faint-hearted, let me just say that the paper changed from stuffy and statist, and the target became the reader as opposed to sources and peers. I recall that lunch at Darryl’s enviable, first-floor home on the seafront—the D’Montes once reputedly owned ‘half of Bandra’. It was the crucible of the coup, and as each new ‘joinee’ materialised at the top of the stairs, an excited gasp of ‘You too!’ went up. Shanta Gokhale and I had rejoined the Times Group, Kalpana Sharma was a new comer. As senior assistant editors, we helped Darryl deliver a punchy paper on real issues, many of which were his personal passions. He espoused the environment , for example, before it became one more cause with a designer label.

Considerable politicking had preceded my return, but I knew I had a friend in Darryl who simply couldn’t be bothered by intrigue. He asked me to write the cover story for the sesquicentennial supplement, and made it a point of telling me to give it substance not mere style. The piece was on the very different Bombay to which I’d returned after nine years back in Calcutta, and thanks to his instruction I did far more legwork that I’d originally intended. And was rewarded with a ‘sign in blood to promise me that you’ll join’. It was his idea to start a tongue-in-cheek regular feature on the back page,‘Backword‘, and through it we discovered a surprising number of satirical writers,

During the ’92-93 riots, he advised me to say on my side of town and report from there. It was among the most searing of assignments. When I began to write in depth on the challenging issue of HIV-AIDS, Darryl readily, and uniquely, conceded to my request not to do only the sensational stories but also quiet ones to temper the stigma. Socially sensitive, he understood that this was too complex a tragedy to be treated like any other journalistic pursuit. You must remember that in those early days not only was it difficult to get any information, comments or expertise from doctors, sociologists and sex workers, but after you’d penetrated those walls of ignorance and fear, editors were too squeamish to print. Dilip Mukerjee who handled the Edit Page, consistently refused to let me do a main ‘3,4,5’( the main edit article) on AIDS, and would relegate it to the margins of a ‘7,8’.

Finally, Darryl was a professional and a gentleman, above any pettiness, politics or jockeying. Not too many about whom you can say this so unequivocally.

—Bachi Karkaria, Journalist, columnist and writer

Darryl, the Media Critic

Darryl D’Monte was an unsparing critic of the way the profession he belonged to conducted itself. Back in 2013-14, he wrote a scathing critique of the media business, tentatively titled ‘Presstitution: How the Media Sold Itself’. Unsurprisingly, his publisher got cold feet and the manuscript never saw the light of day. He sent me tricky paras with the publisher’s comments. The most frequent one was, ‘is it necessary to name?’! He wanted to know what I made of those paras. I told him mildly that much of it was roundly defamatory even if true.

Alas, not many editors of the Times Group have been quite so forthrightly critical of some of its practices. And he never got used to the Times Now’s approach to journalism. Some spluttering mails still reside in my inbox! Pity so many of us now take the channel’s excesses in our stride.

—Sevanti Ninan, founder-editor of The Hoot

The Fierce Environmentalist

Darryl D’Monte, editor of various publications and one of India’s best known environmental journalists, has both inspired and trained a slew of journalists who now occupy the top echelons of the profession. He edited the Sunday Magazine ofThe Times of India for a decade—from 1969 to 1979. It was in the later years of the seventies that I joined his team as a lowly sub-editor and was witness to his earliest phase as an environmental journalist, deeply interested in themes like the threat posed to Bombay residents by the Tata thermal power plant in Chembur, or the battle to save the Silent Valley. Writing in the second State of India’s Environment 1984-85 brought out by the Centre for Science and Environment, he saw the Silent Valley resistance as a ‘silent success’, the “fiercest environmental debate in the country (that) is likely to establish a precedent when ever any major development project—particularly a dam —threatens the ecological balance”. His seniors at the Times, including the venerable Shyam Lal, often looked askance at his choice of subjects showcased in the magazine. I remember well how, when he carried a piece on a bus that fell into the Vaitarna River, as a lead, he had to face sharp criticism from the boss. But the piece reflected his penchant for highlighting seemingly innocuous events to sketch the broader reality of people’s everyday lives and the scenarios in which they played out. It was an approach that led him to emerge as a major environmental crusader in his later years.

—Pamela Philipose, Public Editor, The Wire

Darryl, the Mentor

For journalists like me who joined the profession in the 1980s and were interested in so-called off-beat subjects (that’s how health, science and environment were referred to then), some bylines were must to follow. This list included Anil Agarwal, Darryl D’Monte, Bharat Dogra, Usha Rai, Dr K S Jayaraman and L K Sharma. They were all established names and younger lot looked up to their work for inspiration. Only later in later years one got a chance to meet and interact with them. I first met Darryl when I went to cover the UN Conference on Environment and Development (popularly known as the Earth Summit) held in June 1992 at Rio de Janeiro in Brazil. He had come from Bombay where he was based and the rest of us were from Delhi. Since then I have remained in touch with him, meeting several times during various professional engagements. Much later I came to know about his serious body of work other than what appeared in the Times of India. His work has been referred to in contemporary environment histories written by historians Ramachandra Guha and Mahesh Rangarajan. It is a rare occurrence indeed.

Darryl mentored a whole generation of journalists interested in covering the environment through the platform he created and nurtured till his very last days, the Federation of Environment Journalists of India. Through this network, he shared ideas, press releases, and information about fellowships and other opportunities, The network has brought together dozens of journalists across the country, going beyond the metros. He guarded the network against misuse for ‘greenwashing’ purposes by corporates and welcomed criticism. Hopefully these values will be preserved.

—Dinesh C. Sharma, Managing Editor, India Science Wire

Darryl D’Monte, a passionate journalist who lived by his convictions, left a lasting legacy

I never thought I would be writing an obituary about a friend and a colleague. Darryl D’Monte — journalist, author, environmentalist, human rights activist, and, above all, a good human being has passed. He died on March 16 in a hospital in Mumbai, a city he lived in, loved and fought to save from environmental destruction.

I knew Darryl for decades, as a fellow journalist with whom I worked for a short period in a newspaper, but more than that as a person with whom I shared many common concerns. Apart from his stints as an editor in Indian Express and Times of India, it is Darryl’s pioneering work as an environmental journalist that will be long remembered.

When he wrote about the Silent Valley controversy in the 1970s, where a dam would have destroyed precious biodiversity including the habitat of one of the world’s rarest and threatened primates, the Lion Tailed Macaque, the concept of “environmental” journalism was unknown. Yet, it is the controversy surrounding the dam in Kerala, and the prospect of habitat destruction, that yanked the issue away from conservation to questioning developmental policy. Eventually, the campaign to save the area led to the creation of a national park that would be excluded from the project area of the dam. In his book Temples or Tombs: Industry vs Environment (1985), Darryl has recorded this early environmental battle between the interests of saving the natural environment and the demands of development.

Although Darryl worked for much of his life in mainstream media, he never gave up his convictions on environment, human rights, civic and urban issues and on the rights of the most marginalised. Indeed, being a “committed” journalist was a label Darryl wore unapologetically. Through his reporting, he established that even if we, as journalists, have strong convictions, we can report with rigour and professionalism. His environmental reports stood out for the absence of polemics and for the thorough research that they contained. This kind of reporting set a gold standard for generations of journalists that have followed in his footsteps.

Darryl consciously mentored others. In the cut-throat competitive world in which journalists operate, this stood out then, and stands out even more now, as an unusual trait. But he was more concerned that the issues — whether to do with loss of biodiversity, destructive developmental policies, or climate change — were addressed by many more journalists than just those of his generation. By setting up the Forum for Environmental Journalists (FEJI), Darryl extended support and opened up opportunities for scores of journalists, many from outside the big metros who are not plugged into professional networks, to be trained in environmental reporting.

It is the city of Mumbai, with which Darryl was closely engaged, where he is most remembered and cherished. In Bandra, where his family has lived for generations, he was a known person, actively engaged in civic and cultural affairs — always ready to battle against insensitive and environmentally destructive developmental plans initiated by the municipality or the state government.

Till the end, Darryl never tired of raising the red flag on this. His most recent intervention was questioning the wisdom of building a coastal road to accommodate the needs of a small, well-heeled population owning private vehicles at the cost of the livelihoods of Mumbai’s fisherfolk, its coastal environment and the needs of the majority who have to contend daily with crumbling infrastructure. Unfortunately, the state government is determined to push ahead with the plan and the courts, so far, have not been sympathetic to the pleas of the fisherfolk.

There is never a good time for anyone to go, but this was not a good time for Darryl to go. His sane voice is needed today more than ever before. As this country hurtles towards becoming a violent and fractious society, where the voice of people at the margins is drowned, and where saving the environment is just empty words as policy forges ahead to destroy it, the passion of journalists like Darryl D’Monte is irreplaceable. One hopes the legion of younger journalists he mentored will carry forward his legacy.

source: Indian Express

—Kalpana Sharma, Independent journalist, columnist and writer